Portal Giraldo, of the Guillermo Gaviria Echeverri Tunnel, which will be the longest in Latin America. COURTESY GEOTÚNELES.

Engineer Antonio José Rodríguez Jaramillo. President, Colombian Association of Tunnels and Underground Works ACTOS. Technical Manager, Geotúneles SAS Engineer Carlos Eduardo Mendoza Oliveros. Project Coordinator, Geotúneles SAS

The Guillermo Gaviria Echeverri Tunnel (Túnel del Toyo) is under construction. With a total length of 9.73 km, it will be the longest road tunnel in Latin America, as well as the one with the greatest coverage (887 m), which breaks paradigms in Colombia regarding the execution of subway works of significant diameter, coverage and length, and excavated in highly complex geological environments. In addition, the current execution in record time exceeds the work schedule, all accompanied by advanced techniques in its design and construction.

The project brings together the experiences and techniques that tunnel engineering in Colombia has acquired in the last two decades, making it a reference for the Latin American region.This article will describe the history of the Highway to the Sea, a longing of the people of Antioquia that goes back several decades to have a road connecting the seaport in Urabá with Medellín, as well as the main characteristics of the tunnel in terms of its civil and electromechanical components.

The Vía al Mar

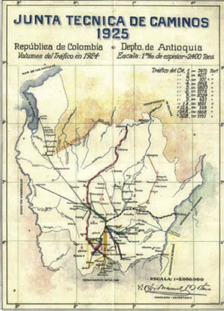

The origin of the road to the sea dates back to 1925, when the Department of Antioquia undertook this project of gigantic proportions for the time, initially contracting a section of the work with the New York construction firm R.W. Hebbard & Co. Hebbard & Co. However, the road had several early detractors who argued that the road was unnecessary because the route of the Western Railroad was already consolidated, which guaranteed access to the sea. Antioquia had been one of the most prosperous regions of Colombia and had always depended economically on the Magdalena River to import and export its products, for which reason the Department sought, starting in 1930, that the Nation finance part of the work; for this purpose $20,000 per kilometer was allocated. 000 per kilometer, arguing the following “…WOULD BE AN EMINENTLY PATRIOTIC INVESTMENT TO DEFEND ITS INTEGRITY, TO PROVIDE EMPLOYMENT FOR ITS CHILDREN, TO CREATE WEALTH, AND TO PREPARE FUTURE CARGO, WHICH INSTEAD OF SERVING TO TAKE TRAFFIC AWAY FROM THE RAILROADS IN ANTIOQUIAN TERRITORY, WILL INCREASE THE MOVEMENT OF INTERNATIONAL AND INTERDEPARTMENTAL COMMERCE THROUGH THEM…”1.

The 1940s was one of the most difficult decades for the construction and improvement of roads and highways in the country. For this reason, the Highway to the Sea continued in the project stage, because the connection between Medellín and the Gulf of Urabá was not efficient and, in addition, it did not compete with the exit to the Caribbean through the Magdalena River. In the following decades, and up to the middle of the 21st century, the project would continue to advance with multiple technical and economic drawbacks common in the second half of the 20th century, depending on the plans of the departmental and national governments. Subsequently, towards the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, and with the emergence of Colombia's economic opening to the world, the region began to experience a new impulse in the modernization of the old Road to the Sea, a process that would lead to materialize the construction of the first road tunnels on that road, initially with the La Llorona tunnel, of 435 meters in the municipality of Dabeiba - inaugurated in 1995 - and successively with the West or San Jerónimo tunnel of 4,603 meters in the municipality of Medellín. 603 meters in the municipality of Medellín, inaugurated in 2005, where the construction of a second tunnel is currently underway.

As part of the National Government's initiative called "Highways for Prosperity", which seeks to build a series of highways for speeds of 80 km/h throughout the length and breadth of Antioquia, the Highway to the Sea initiative was included in several sections: from Medellín to Santa Fe de Antioquia the ANI’s Sea Road Concession 1; then and up to the municipality of Giraldo, Section 2 of the Toyo Tunnel project and its access roads, in charge of INVÍAS, comprising eleven tunnels, including the 1.3 km Tonusco Tunnel. Between Giraldo and the municipality of Cañasgordas, Section 1 is currently being built by the Government of Antioquia, the Municipality of Medellín, ANI and INVÍAS, which includes the Guillermo Gaviria Echeverri Tunnel and 6 short tunnels. Finally, from Cañasgordas to the Gulf of Urabá, Sea 2 Road Concession is being carried out by ANI, with the construction of 13 tunnels, including the 2.1 km long Fuemia tunnel. These tunnels will cross the western mountain range and its rugged geography to reach the Urabá region, where it will connect with the Port of Antioquia in the municipality of Turbo. Travel time between Medellín and the Port in Urabá will be 4 hours and 30 minutes.

Road to the Sea, project 1925. TAKEN FROM EAFIT, 2014.

The Guillermo Gaviria Echeverri Tunnel

The Guillermo Gaviria Echeverri Tunnel (GGE) is a bi-directional road tunnel with a subway excavation length of 9,730 meters. The subway works for the tunnel network and galleries exceed 20 km and constitute the longest similar excavation in Latin America for road works. It is also the road tunnel with the greatest surface coverage -887 m- and therefore presents high geostatic stresses which, added to its geological and tectonic environment, add up to highly complex conditions that pose a challenge for its construction.

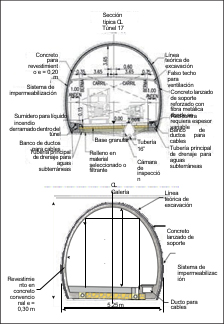

As for the service section, the GGE Tunnel will have 1.0 m wide platforms, 3.65 m wide lanes and a 0.35 m over-width. The gauge is 5.0 m, over which a false ceiling will be installed to separate the upper section known as the canton, where fresh air will be ventilated and stale air from vehicular traffic will be evacuated through two buildings in the portals that will inject air; this ventilation system is called semi-transverse, similar to the one used in the first Túnel de Occidente. This led to excavating portals with heights of up to 45 m and stabilizing them with active anchors, the first major challenge for the project.

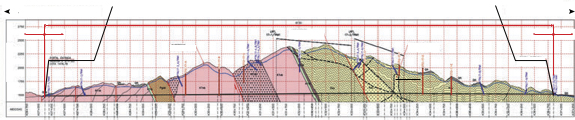

The GGE Tunnel is excavated with two fronts called Giraldo, towards its entrance, and Cañasgordas towards its exit. Each of these fronts is excavated in two different geological environments and their contact will be towards the middle of the tunnel, in the zone of maximum coverage. From the Giraldo front, igneous rocks of the Barroso Volcanic Formation are excavated, characterized by hard basalts and diabases with good to excellent geomechanical characteristics, although some fractured and fault zones have been foreseen where their quality decreases. As for the Cañasgordas front, there are sedimentary rocks such as mudstones and sandstones of the Penderisco Formation, whose geomechanical conditions are very poor to regular, highly fractured and folded, with thrust zones and volcanic intrusions. The Cañasgordas Fault, which has an orientation almost parallel to that of the tunnel, has tectonized the rock massifs to be excavated, and there is also the influence of the Higuerona Fault towards the first middle third from the entrance, which together with the contact of the two formations, constitutes the most complex areas for excavation and stabilization. The main challenges to overcome are special phenomena that occur in this type of excavations: severe to extreme squeezing in the face of tectonic stress concentration, rock bursting, abundant water flows accompanied by material dragging in weak contact zones, dislocations of large blocks, chimney type overexcavations and high geostatic stresses that, in the face of low geomechanical conditions of the sedimentary rocks and fault zones or breccias with a soil type behavior to be excavated, are in states of plasticization.

Geological profile of the Guillermo Gaviria Echeverri Tunnel. COURTESY GEOTÚNELES S.A.S.

Service section of the Guillermo Gaviria Echeverri Tunnel and its parallel rescue gallery. COURTESY GEOTUNNELS S.A.S.

Based on the geotechnical exploration campaign and the characterization of the geological massifs to be excavated, 18 types of supports designed for the tunnel and the same number for the rescue gallery and its connections were planned, in addition to the supports for special sections such as the parking bays and the SOS and fire-fighting niches. The tunnel excavation is carried out by the drill and blast method, taking into account the philosophy of the New Austrian Method NATM and the observational method, with a flexible design that allows to quickly adapt the support elements required by the tunnel according to the monitoring of the geotechnical instrumentation installed. The supports have been differentiated by coverages less than 300 m, between 300 to 600 m and greater than 600 m, for each of the terrains to be found, from Type I terrain (one of the few tunnels in Colombia that have it) to Type V* terrain designed based on the experiences and learning obtained from the Colombian tunnels, to overcome conditions of extreme geological and geotechnical complexity.

The tunnel has a waterproofing system and a system for capturing infiltrated water to convey and deliver it to treatment plants, so that the liquid is returned to the region with minimal environmental impact. Likewise, in the areas where water flows are expected, an injection design has been designed to waterproof the massif in order to avoid affecting the natural hydrogeological conditions.

It is important to note that the entire length of the tunnel will have a conventional concrete lining designed to withstand additional long-term deferred loads, which ensures that the tunnel will be in optimum condition for service for 100 years. The concrete is reinforced with steel bars and synthetic microfibers have been added to control the phenomenon of SPALLING or concrete bursting, in anticipation of a fire inside the tunnel.

The project achieves high safety and service standards that put it on a par with European tunnels, as it will include all the elements recommended by the European Union's Directive 2004/54/EC, as well as the American NFPA 502 standard for the firefighting system. There will be 92 SOS booths and 116 niches with fire hydrants, as well as nine parking bays spaced every 1,000 m (3,000 ft). The vehicular and pedestrian galleries will allow rescue vehicles to access the tunnel every 400 m through the gallery parallel to the tunnel in the event of an accident inside. Other state-of-the-art ITS and firefighting systems have been incorporated into the tunnel, such as voice and video systems, infrared cameras, and gas concentration meters, among others, coordinated from an operation and control center with a fire station, ambulances, and rescue vehicles.

As of November 12, 2020, 41% of the excavation had been completed, equivalent to 4 km. COURTESY GEOTUNNELS S.A.S.

The work in numbers

The quantities of GGE work show its magnitude and imposing nature: 1.5 million m3 of excavation, 170,000 m3 of excavation of the two portals to generate the platforms necessary to build the ventilation buildings, 70,000 m3 of shotcrete with fibers to reinforce it, 700,000 m3 of hydraulic concrete for cladding, pavement, platforms and other structures, 14,000 tons of reinforcing steel, 4,000 tons of steel arches in TH and HEB profiles in different denominations, 360,000 tons of anchor bolts, 92,000 m of umbrellas for pre-support, 485,000 m2 of PVC sheeting for waterproofing, 350,000 m of different types of piping for handling seepage water, and 22,000 m of prefabricated sumps for collecting liquids spilled inside the tunnel.

Section 1 of the Toyo Tunnel road (GGE) and its access roads is expected to be completed in 10 years, of which six years have been allocated for the construction of the tunnel. The work began in January 2018 and as of November 12, 2020, 41% of the excavation had been executed, equivalent to 4 km, in addition to having challenging goals such as achieving the excavation of half of the tunnel in December 2020 and the complete excavation by the end of 2022, one year ahead of schedule.

Conclusions

The longest road tunnel in Latin America, which will be the heart of the road to the port of Urabá, should be in service before the end of this decade. It is one of the most ambitious projects to boost the economy of the department of Antioquia and Colombia. The complexity that has characterized this tunnel is high, but it is not impossible to carry out, as some traditional consultants of the local environment stated with skepticism.

Fortunately, the GGE Tunnel breaks every day paradigms that prove otherwise, which reminds us of the legacy of Alejandro Lopez, whose thesis on the La Quiebra Tunnel demonstrated 121 years ago to his mentors that it was possible to excavate long tunnels in Colombia. By applying state-of-the-art technology, focused and meticulous designs that are perfected every day on site, the Colombian tunneling apprenticeship has managed to cross its mountain ranges well. The collaboration of more than a thousand people who have participated in the project demonstrates that when megaprojects are well structured, planned and executed cooperatively and without vices, their only destiny is to be a resounding success.